•Recent news about an American woman experiencing “brain fluid leak” after a COVID-19 nasal test has raised fears about undergoing swab testing.

•However, the case is exceptionally rare, and was mainly due to an undiagnosed defect at the base of the patient’s skull; a person without that condition should have nothing to fear from COVID-19 swabbing.

•The Philippines is now on the list of 20 countries with the most COVID-19 infections worldwide, highlighting the importance of undergoing proper testing and contact tracing.

Last October 2, news about a newly published paper in the peer-reviewed medical journal JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery made the rounds online. The paper presented the case of a woman from Iowa, U.S. in her 40s, who opted for a nasal swab test before undergoing hernia surgery. After swabbing, the patient noticed clear fluid leaking from one side of her nose; shortly after that, she developed neck stiffness, headache, vomiting, and photophobia (aversion or insensitivity to light). Many local and international news outlets published the story with the headline “COVID-19 test caused brain fluid leak in US patient with rare condition” (or some equally graphic variation).

Unfortunately, this caused quite an uproar on social media, with many users decrying the “dangerous” COVID-19 nasal swab test. Worse, this has prompted COVID-19 skeptics to use the story as an argument against COVID-19 testing, downplaying the seriousness of the virus and saying that the testing procedure itself is far more risky.

But is this patient’s case really proof that COVID-19 swab testing is dangerous? And more importantly, should we be afraid to undergo nasal swab tests?

Fact is, there’s far more to this story than one can get from the headline, and it all points to one truth: As long as they’re carried out properly, the average person has absolutely nothing to fear about COVID-19 nasal swab tests.

Did the COVID-19 swab test really cause brain fluid to leak?

As it turns out, this incident only happened because of a mix of highly improbable events, including the fact that the patient actually had a rare and undiagnosed condition.

“The swab did cause the leak from what we can tell, but only because there was an undiagnosed herniation or sagging of brain tissues through a hole in the bone of the base of the skull,” explained senior author and otolaryngologist Dr. Jarrett E. Walsh in an interview with FlipScience.

Walsh, who took care of the patient at the University of Iowa Hospital, emphasized that the swab “did not puncture the skull base in this case.”

Many years ago, the patient had received treatment for intracranial hypertension, a build-up of pressure of the fluid surrounding the brain (cerebrospinal fluid or CSF) which, if left untreated, can cause severe headaches and even permanent blindness. As time passed after her procedure, she developed an encephalocele, a defect at the base of her skull (or the bone at the top of the nose) which allowed part of her brain’s lining to protrude into her nose, making it possible for foreign objects—like a swab, for instance—to rupture it. It’s also possible to be born with this defect, but it’s extremely rare; according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), only 1 in 10,000 babies in the U.S. are born with an encephalocele each year.

“This very rare event should not scare anyone away from testing that can be critical to diagnosis of this virus,” Walsh told FlipScience. His team discovered the encephalocele after reviewing her CT scans from 2017—it was undiagnosed for years—and performed surgery to repair it; the woman has now fully recovered.

‘A little bit high’—but still not enough on its own

In addition to the encephalocele, the swabbing technique used was incorrect, as the swab was positioned “a little bit high.” Majority of existing swab testing protocols specify following the path of the floor of the nose instead of pointing the swab upward.

However, it’s important to understand that under normal circumstances, this alone would not have caused the leak.

“There are, in unoperated nasal cavities, areas that are very thin and could be punctured,” Walsh elucidated, “but even still, would require significant force—something that any tester who is trained should be aware not to do.

“[A similar incident] can happen, but [it] would be exceptionally difficult, and would only be the result of improper technique.”

Another important piece of information about this case that one can’t know from just reading the headline: The patient actually had a nasal swab a month earlier, on the same side as her encephalocele, without any problem. Additionally, upon admission at the University of Iowa Hospital, the patient had another nasal screening swab, which went without a hitch.

“The average person has nothing to fear,” stressed Walsh. “As evidenced by our patient, even with this defect and having had a leak, a safe swab was able to be performed not once, but twice!”

Prevention through good protocol

Identifying the patient’s defect helped Walsh and his team figure out how the injury could have happened. Basically, if the patient’s encephalocele had been identified earlier, it would have been fixed. This would have reduced her risk of sustaining a swabbing-related injury.

However, Walsh does not recommend radiographic screening before testing. Screening sites may not have access to the patient’s full medical records (or even the luxury of being able to review them before testing). Plus, it’s an additional burden to testers who likely have to perform hundreds of tests per day. Fortunately, there’s a simple solution to this: a quick update to the screening questions.

“I think screening questions to the patient geared towards skull base surgery, extensive sinus surgery, or prior CSF leak will be more than enough to prevent injury,” said Walsh. “Most people do not have extensive sinus surgery. Even fewer people have had skull base surgery. Even fewer have undiagnosed skull base defects.”

For patients who have had extensive sinus or skull base surgery, Walsh suggested availing alternatives to nasal swabbing, such as oral testing, if available. “If there is particular concern, I encourage you to talk to your physician about any potential added risks of obtaining a test. For the exceeding majority, there are none. It is exceptionally safe when done correctly.”

For testing centers that don’t offer any other options, though, sticking to appropriate testing protocols would be more than enough to safely carry out a nasal swabbing. “I would encourage testers to take a moment of pause prior to testing to ensure the correct technique is used,” Walsh added.

“What is needed is adherence to good protocol.”

Are COVID-19 swab tests in the Philippines safe?

During an online press briefing, the Department of Health (DOH) assured the public that the healthcare workers conducting COVID-19 testing in the Philippines undergo proper training.

“We train the people conducting these tests in order to avoid these incidents,” according to DOH Undersecretary and spokeswoman Maria Rosario Vergeire.

Vergeire also said that carrying out swab tests properly requires having the right supplies, swabs, and procedures. “We have licenses for our facilities, and we monitor and conduct on-the-spot checks, even for those doing remote collection. So I hope that our fellowmen would not worry.”

Fear the virus, not the test

“Our goal in this paper was not to incite fear,” Walsh shared with FlipScience. “Unfortunately, people will take what they want from headlines and not review the source material.”

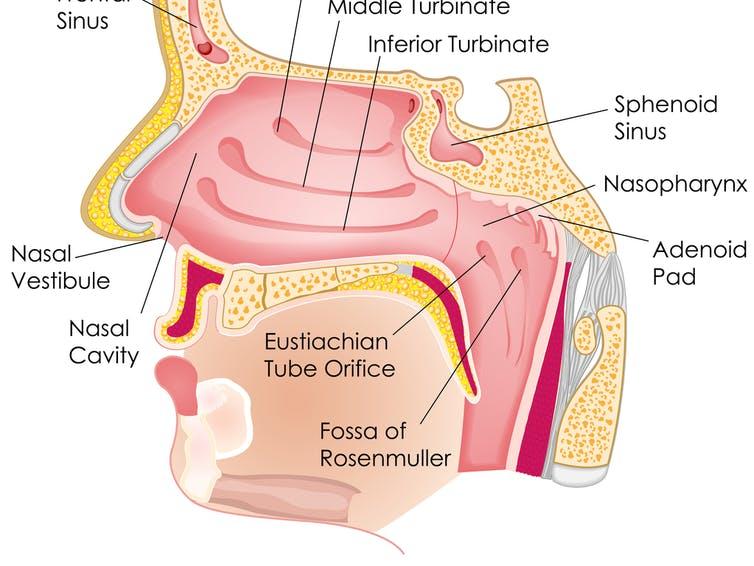

In sharing the case study with the rest of the world, Walsh and his co-authors wanted to highlight the importance of using the appropriate testing technique—the same technique that, according to Walsh, is used on a daily basis by physicians and nurses in placing feeding tubes, gastric suction tubes, and endoscopes without issues. “It all comes down to knowledge of nasal anatomy.”

Walsh also expressed disappointment regarding the negative reactions he observed on social media. “I have unfortunately seen some of the secondary postings on social media and other outlets, with many people screaming that ‘they knew all along this was a dangerous test’ and that ‘the virus isn’t that big of a deal when the test can cause a problem like this’. I would say to those people that they have missed the point of the article.”

As of October 4, the Philippines has 322,497 COVID-19 cases, with 273,079 recoveries and 7,776 fatalities. Despite over 200 days of being placed under quarantine, the Philippines is now among the 20 countries with the highest number of COVID-19 infections worldwide.

“For those who are concerned, there are far more potential life-threatening consequences of coronavirus—and consequences to others for not being tested.”

References

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaotolaryngology/fullarticle/2771362

- https://mb.com.ph/2020/10/02/covid-19-test-caused-brain-fluid-leak-in-us-patient-with-rare-condition/

- https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1343140/doh-allays-fears-over-covid-19-swab-testing-after-us-incident

- https://theconversation.com/no-you-cannot-pierce-your-brain-with-a-swab-test-147364

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.