By Rainielle Kyle Guison, Amiel Earl Malabanan, John Gherald Navera, and Sophia Romilla

Clear skies, humid air — it’s a bright summer morning, and Mang Apollo Aguilar has just decided that it’s that time of the season to plant rice again. Mang Apollo is a 58-year-old farmer from Mabitac, Laguna, who has been farming since the ’90s, following in his parents’ footsteps. In his 30 years of farming, he developed the instinct to identify the best time to plant and grow rice crops.

“Sa tagal ng panahon [na nagsasaka kami], nagre-rely na kami sa experience kung kailan magtatanim ng palay. Nasa panahon kasi yan kaya ‘yun ang basehan namin.”

(For years [that we have been farming], we have relied on our experience in determining the season for planting rice. We monitor the weather which serves as our basis.)

Apart from their instinct, Mang Apollo and the other farmers from Mabitac still practice other traditional farming techniques. They still endure the harsh sun to plant seedlings, apply fertilizer, and spray pesticides, among other tasks. They also use carabaos to plant in deeper areas of the farmland. It involves tedious work. As the Filipino folk song goes, “Magtanim ay di biro.” (“To plant rice is not a joke.”)

When modernization becomes an option

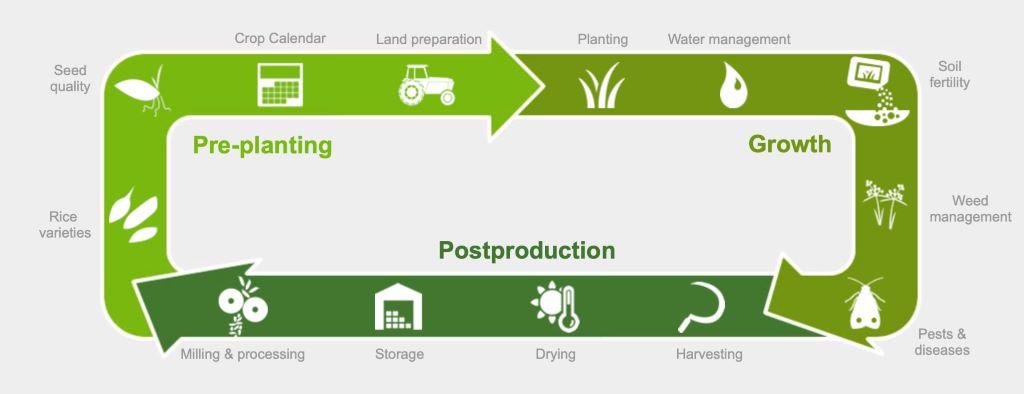

Because of the tedious processes in agriculture, farmers have learned to appreciate the rise of technology and the modernization it brings to agriculture. On Mang Apollo’s farm, certain farming practices have been optimized with the help of machinery, specifically in the post-production stage. This stage includes harvesting the rice grains that we cook for our daily meals.

Harvesting rice is a complex process. It involves many steps to ensure that we have a good bowl of rice on our dinner table. Once the rice plant is ready for harvest, around 80% of the grains should be yellow instead of green. If you try to chew the rice grain, it should be firm to hard and not brittle.

Reaping is the process of cutting the plant’s stalk. To understand this better, imagine the rice plant as tall grass that has seeds on top. The task is to collect the seeds, both for food preparation and for the process of planting rice again in the future.

After obtaining the grass bundles, they will be left to dry under the sun, since the stalks are still wet due to moisture. The next step is to haul them, which is essentially moving the grass bundles into a different location where the seeds will be separated from the rest of the plant. Removing the seeds involves either shaking the grass bundles or hitting them against a hard surface. This process, called threshing, will make the seeds fall out of the grass stalks. After collecting the seeds, the next step is to clean them by sifting or winnowing, so that empty grains, dust, and other debris could be removed.

And there you have it — we have collected the seeds from the tall grass, just like how farmers harvest rice from a rice field.

On Mang Apollo’s farm, post-production processes are done using a mechanical rice harvester which has helped them avoid grain damage so that they can harvest more rice with better quality. Some processes mentioned above like field drying quickly deteriorate the quality of the rice grains which results in harvest losses. Luckily, many farmers have received post-harvest machinery from the Department of Agriculture such as rice harvesters and dryers.

As Mang Apollo put it: “Pabor kami d’yan [sa post-harvest machinery] dito sa farm namin kasi napapabilis ang proseso na tatlo hanggang apat na araw na pag-aani, tapos magbibilad pa. Ngayon, kapag inani ng harvester at gumamit ng mechanical dryer, ilang oras lang, ayos na. Madaling maging pera, sa madaling salita.”

(“We favor it [post-harvest machinery] here at our farm because it speeds up the three- to four-day process of harvesting and drying. Now, when we use a mechanical harvester and dryer, it would only take us a few hours. In simpler words, we earn money quicker.”)

Because of those benefits, Brgy. Mabitac’s Municipal Agriculture Office (MAO) is open to participating in modernization. In fact, MAO’s Officer-in-Charge Engineer Johnviefran Patrick Salvador mentioned that they recently participated in a project with the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) called SARAi (Smarter Approaches to Reinvigorate Agriculture as an Industry in the Philippines).

SARAi: The bridge between traditional practice and technology

Project SARAi is a research program implemented to provide local farmers with useful information that would improve their harvest.

Specifically, SARAi assists farmers by letting them know what the weather would be like, what kind of crops they should plant for the season, what soil type they should use to improve their crops’ quality and yield, and what kinds of pests and diseases their crops are susceptible to. The project team also developed drones that allowed them to monitor if their crops were still healthy or needed more care. With the continuous innovation of SARAi, they managed to use satellites that allowed them to forecast the rainfall for the week, along with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) that helped them identify the farmlands that cater to specific crops.

SARAi’s partnership with Brgy. Mabitac during the dry and wet seasons in 2022 focused on capturing satellite images of their farmlands.

“Wala lang naging masyadong participation ang aming farmers [sa proyekto], pero yung data naman ng Project SARAi ay na-integrate namin doon sa Municipal Development Plan, kaya nakatulong ito sa municipal level,” Engr. Salvador explained.

(“Our farmers didn’t have a lot of participation [in the project], but we were able to integrate Project SARAi’s data with our Municipal Development Plan, so it was helpful on a municipal level.”)

He also said that the reason farmers may not have fully understood the project’s implications is that the partnership was more focused on data collection than on the direct use of SARAi’s technology.

As of now, their partnership is on pause since the project is still waiting for funding renewal. Project SARAi has been primarily funded by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD) since November 2013. Through the years, the project has successfully partnered with 11 state universities and colleges and six national government agencies, apart from local communities.

In an interview with UPLB Professor Nelio Altoveros, one of SARAi’s project heads, he shared that the project has updated its ultimate goal from delivering advisories to establishing regional and community-level SARAi hubs that farmers can visit to get real-time information and report initial farm conditions. Ideally, farmers can also take photos of pests they see in their farms to have them evaluated quickly so that they can easily get rid of them and avoid them in the future.

“SARAi also continues to operate because many different scientists and researchers are passionate about Project SARAi, especially because of its direct impact on our stakeholders,” Altoveros said. He also added that they are motivated to work on how they can further develop the project and its technologies, as SARAi is one of the many DOST-funded projects that has the ability to transform the country’s agriculture industry in the future.

Altoveros shared that he has been with SARAi since 2018, and that he will continue to support it despite working pro bono as a regular faculty member along with his colleagues, calling SARAi their “passion project.”

On the other hand, Brgy. Mabitac’s local farmers have yet to use SARAi’s technological innovations. Engr. Salvador expressed that they are looking forward to how these can simplify the complexities of farming. This is because SARAi’s technology does not replace farmers in the field, which is one of the concerns faced by local farmers that usually makes them reluctant to modernize.

According to Mang Apollo, they keep in mind that farmers need their jobs to support their families, which is why they don’t fully mechanize all their processes.

“‘Pag tatanungin mo ‘yung karamihan ng magsasaka, hindi naman namin inaalis ‘yung mananananim para naman hindi nawawalan ng hanapbuhay yung ating magsasaka. Ang nawala lang yung mga mag-aani na mano-mano, kasi mas pabor sa aming magsasaka ‘yung mabilis na proseso, lalo na kung gusto mong mag-second cropping,” Mang Apollo explained.

(“If you ask most of the farmers, we don’t lay off those who plant in the fields, so that our farmers don’t lose their livelihood. The only farming role that we removed is those who harvest manually because we favor the faster process with machinery, especially if we want to do second cropping.”)

One of Project SARAi’s main innovations is the weather monitoring system. There are 20 weather stations set up across the country, two of which are inside the University of the Philippines Los Baños. These can guide the planting and harvesting calendars of farmers through data. While they have traditionally relied on their instincts, a weather report based on science that is readily available on SARAI’s website can greatly improve the accuracy of their farming processes.

Envisioning potentials

In an interview with ABS-CBN, the Department of Finance said that the Philippines is eyeing satellite mapping to help fight inflation. One of the technologies mentioned by the agency was Project SARAi, as its value proposition of maximizing crop growth can help the Philippine GDP.

In February 2023, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. approved Executive Order 17, or “Revising the Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Scientific Career System under Executive Order 901 (S. 1983),” which indicates that the State shall prioritize research and development, as well as scientific innovation and invention. This should ensure the continuation of projects like SARAi.

Meanwhile, Altoveros emphasized the importance of LGU participation in the project, especially in facilitating the farming communities. Moreover, they can also help foster a positive attitude among the farmers toward Project SARAi.

The Philippines has much potential for further growth and development, particularly in the agricultural sector. While projects like SARAi provide a much-needed boost, it is equally urgent for stakeholders to become more open to modernization. Indeed, the people behind the success of SARAi — the farmers, technologists, and experts — are proof of what we can achieve when traditional practice and agricultural technology meet.—MF

References

- Postproduction – IRRI Rice Knowledge Bank. (n.d.). http://www.knowledgebank.irri.org/step-by-step-production/postharvest

- Warren de Guzman, ABS-CBN News. (2023, April 4). Diokno eyes satellite tech to fight inflation. ABS-CBN News. https://news.abs-cbn.com/business/04/04/23/diokno-eyes-satellite-tech-to-fight-inflation?fbclid=IwAR2l_SAwVWpbyP8tpxhTJnyAWnjPSbKCY6ankhGLY5UrnGlldvGoHdJQRGQ