•In 1847, a Hungarian physician named Ignaz Semmelweis was the first to realize that improper handwashing could spread diseases in hospitals.

•Despite his success in reducing mortality rates, Semmelweis’ rules on handwashing and disinfection were rejected by the medical community at the time.

•Years after his death, Semmelweis’ findings contributed to the formation of what we now know as the germ theory of disease.

These days, the importance of washing one’s hands is clear, well-defined, and repeatedly emphasized. For something that has become such a basic part of everyday life, it’s almost difficult to imagine a time when people doubted the value of handwashing. It may come as a surprise, then, that it has only been less than two centuries since society accepted handwashing as an essential daily practice—and it’s all because of a man who was determined to save lives, no matter how much his peers tried to put him down.

The handwashing hero

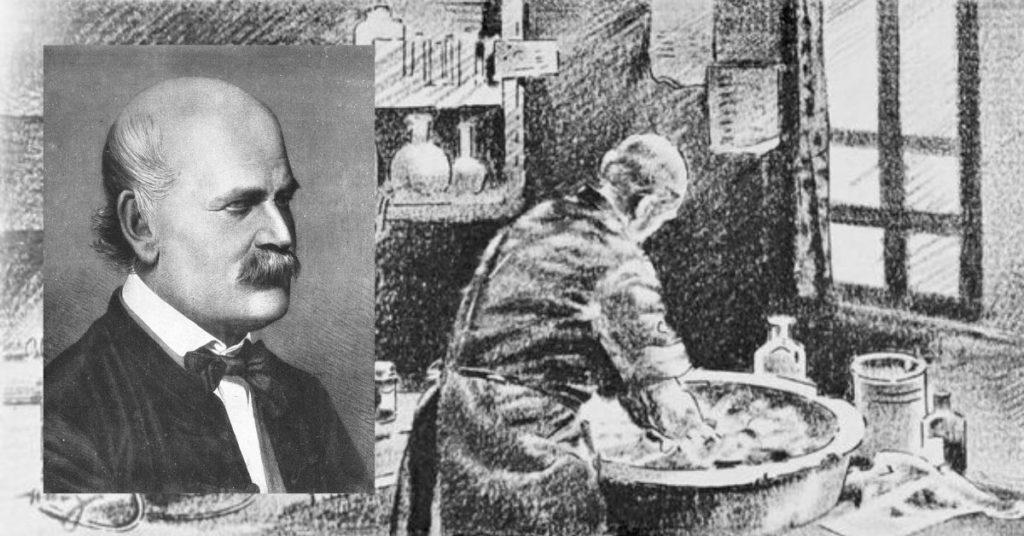

Born on July 1, 1818 in Budapest, Hungary, Ignaz Semmelweis is widely regarded as the “father” of handwashing and infection control.

Semmelweis obtained his doctorate from the University of Vienna in 1844, and officially joined the maternity clinic of the Vienna General Hospital in 1846 as First Assistant (equivalent to Chief Resident) in Obstetrics. At the time, an illness called childbed fever was baffling doctors all over Europe; nobody was sure how the mysterious illness ended up killing new mothers at alarmingly high rates. The disease was attributed to a variety of causes, some as ridiculous as “mothers’ shame” after male doctors examined them.

While Semmelweis was determined to solve this medical mystery, the actual cause eluded him for nearly a year. The key to cracking this case came to him on March 20, 1847, upon his return to the hospital after a trip to Venice. Semmelweis learned that his friend, forensic pathologist Prof. Jakob Kolletschka, died after his finger was accidentally cut during an autopsy. After looking at his friend’s autopsy findings, Semmelweis noted similarities between Kolletschka and patients who had died from childbed fever.

Further examinations revealed that foreign substances (which Semmelweis called “cadaveric particles”) entered Kolletschka’s bloodstream—the same particles that entered mothers’ birth canals through their attendants’ hands. Supporting this idea was the fact that mortality rates were higher in the hospital’s First Division (where physicians and medical students, who participated in autopsies, handled cases alongside midwives) than in the Second Division (where only midwives performed deliveries).

The germination of a life-saving idea

Eventually, Semmelweis realized what was wrong: Physicians and medical students washed their hands with just soap and water prior to examining mothers in labor, which was not enough to remove the “cadaveric particles” (germs). He immediately instituted a new rule: All doctors were to wash their hands and instruments in a chlorine solution to disinfect them. Soon, mortality rates dropped from about 18% to just 1%.

Back then, however, the concept of disease-causing germs was still unknown. Thus, despite the decreased mortality rate, medical professionals were largely skeptical of Semmelweis’ findings. Some were even insulted, finding it preposterous that they, the educated professionals from the upper echelons of society who were much “cleaner” than the poor, could actually have filthy hands that caused diseases. Others found the additional step of disinfecting both tedious and costly. And with the lack of scientific evidence at the time to support Semmelweis’ ideas, bruised egos triumphed over an otherwise effective policy.

A mind poisoned, a man ruined

Semmelweis eventually returned to Hungary, where his emphasis on handwashing helped save the lives of many new mothers. Unfortunately, neither this nor the publication of his numerous articles on handwashing earned him anything beyond mockery and scorn from the medical community in subsequent years.

Some say that this endless rejection took a toll on Semmelweis’ mental health. At this point, it’s difficult to say if it was Alzheimer’s, third-stage syphilis, or emotional exhaustion that pushed him over the brink. Regardless, he was tricked into going into an asylum in July 1865. Reportedly, when he realized this and attempted to escape, the asylum guards beat him savagely, restrained him, and threw him in isolation. Semmelweis died a painfully ironic death on August 13, 1865; it was a gangrenous wound on his right hand, possibly sustained from his beating, that ultimately claimed his life.

Too little, too late

Decades after he was rejected by his colleagues, Semmelweis’ work gained acceptance and recognition. His findings greatly contributed to the development of germ theory, the currently accepted scientific theory pointing to pathogens as the causes of many diseases.

As a testament to his contribution to public health, the Medical University of Budapest renamed itself the Semmelweis University. Now, over a century after his death, we recognize the previously unsung brilliance of Ignaz Semmelweis: a man who, despite wanting nothing more than to do his job, was ridiculed and rejected by his seniors and peers who couldn’t accept the possibility of being wrong.

Cover photo: Jenő Doby (inset); Bettman/Getty

References

- https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/20/health/ignaz-semmelweis-handwashing-discovery-trnd/index.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/18/keep-it-clean-the-surprising-130-year-history-of-handwashing

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/03/handwashing-once-controversial-medical-advice/

- First Assistant

- https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/13/3/233

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.