Vinz is just like any other 4-year-old: really shy at first, but becomes a ball of energy once he warms up to you. His favorite color is orange, which also happens to be his favorite fruit (tied with the banana). He loves Pokémon; he likes to think of himself as Ash, the protagonist, which makes Pikachu his companion of choice.

Vinz is such an ostensibly typical child that if it weren’t for his cleanly shaven head and N95 mask, no one would guess that he had cancer.

A month after his third birthday, in early 2017, Vinz broke out into weekly fevers. His skin even turned a pale yellow, recounts Tin Malubay, his mother. At first, they thought it was dengue; all the blood tests he took, however, found him negative for the infection. The fevers kept coming, so in April that year, they put Vinz ferrous sulfate medication to increase his hemoglobin levels.

Three months later, when his blood chemistry remained unchanged, his doctor broke the horrible news.

Vinz was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a cancer brought about by the abundance of immature lymphocytes (a subtype of white blood cells). Inside the bone marrow, the cancer cells multiply uncontrollably, smothering the normal ones. As a result, the undeveloped cells dominate the child’s body and compromise the immune system.

Two months into her pregnancy, when she wasn’t aware of it yet, Malubay had an X-ray taken as part of a routine health clearance procedure for employment. She often points to this as the reason for Vinz’s condition. However, like all other cancers, ALL is unyieldingly complex. There is no single, identifiable cause for Vinz’s condition. In fact, his father’s smoking could have contributed just as much.

Malubay is a single mother. Her former partner left her just last year, soon after her son’s diagnosis. They were together for 8 years, five of which were cohabitant. The entire time, he was an incessant smoker. She said he averaged 4–5 sticks a day. During weekends, when they’d go out drinking with friends, he could go through an entire pack in hours.

Malubay didn’t and doesn’t smoke, but she didn’t walk away from it either. Her ex smoked freely around her; back then, she didn’t think much of it. After all, they had no children, nor was she expecting. It was their exhaust and their bodies; their problem and their business. What was the worst that could happen?

The intergenerational pollutant

The lit end of a cigarette stick can get as hot as 900° C. At this temperature, almost all of the approximately 7,357 chemicals in tobacco smoke become vapor and pass into the gaseous phase. But when a smoker inhales, that temperature drops, and the heavier chemicals condense into tiny, microscopic droplets. These constitute the particulate phase of tobacco smoke, or what people more commonly refer to as tar.

Inside the body, the smoke blows past the voice box and through the trachea, which splits into two and opens into the lungs. The droplets fill the tiny air sacs at the ends of each branch, where they can diffuse into the blood stream.

From there, it takes less than a minute for the chemicals to spread through the body.

As blood circulates, tar clings to different body parts: the kidneys, the brain, the guts, the heart, and even the gonads. Once in the gonads, cigarette smoke transcends the present, becoming an intergenerational pollutant.

Gametes like sperm cells are produced, mature in, and are stored in the gonads. They hold half of the genetic information passed on to the child. To make a complete set, babies receive two upon conception: one from the mother, one from the father.

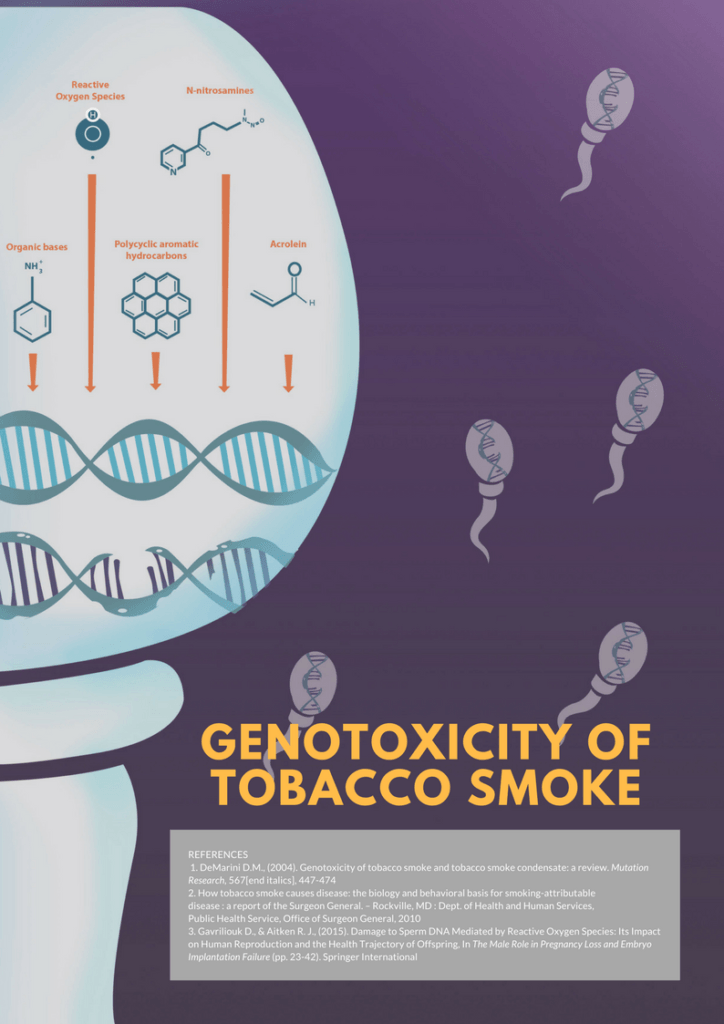

Many different classes of chemicals in cigarette smoke are highly genotoxic. That is, they dig deep into the sex cells and assault the DNA, often dealing permanent harm. One class of tobacco chemicals called reactive oxygen species, for example, burns into the DNA, breaking crucial chemical bonds in the process.

The DNA will try to repair itself. Over time, however, scars will accumulate and, when the sperm meets the egg, will get transmitted to the embryo. Children born from this union are much more prone to conditions like pneumonia, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer.

Illustration by Kel Almazan

Finding the smoking gun

The ability of tobacco smoke to mutate human DNA in any organ is so potent than in a 2004 review, David DeMarini of the US Environmental Protection Agency wrote: “Tobacco smoke is now the most extreme example of a systemic human mutagen.”

This has also been shown epidemiologically, though definitive, irrefutable causal proof remains elusive. In a 1997 study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Ji et al. looked at pediatric cancer cases whose fathers had smoked prior to conception but whose mothers had not.

In these children, the odds of ALL was 3.8 times greater than controls whose fathers had never smoked.

Over the years, several other studies have shown this trend, although to lesser extents. A 2011 meta-analysis of 13 studies by Liu et al. of the University of California in Berkeley showed that the chances of developing ALL were 1.25 times greater in kids whose fathers had smoked prior to conception.

Some uncertainties still remain, though. Most of the studies on maternal smoking and offspring ALL, for instance, have found no significant link between the two. That mothers tend to consume fewer sticks than fathers may be a possible explanation. However, solid conclusions on this have yet to be drawn.

In a 2006 study, Chang et al. also hypothesized that since maternal smoking is known to induce spontaneous abortion, it’s possible that some of the kids who would have had ALL were never born in the first place — a selection bias that eats away at the otherwise significant effect of maternal smoking.

Nevertheless, the evidence seems to suggest that even if the chemicals never physically come into contact with the child, smoking can have devastating repercussions. It’s not just the smoker’s – or his partner’s – business alone.

“Smoking is a pediatric disease,” said Dr Riz Gonzalez, MD, FPPS, chairperson of the Philippine Pediatric Society Tobacco Control Advocacy. “What we know is that the burden is on the adults. But actually, it’s on the pediatric age group. It’s like you planted a tree dipped in nicotine.”

Unfortunately, no such structured data exists for the Philippines. There are estimates for childhood ALL and statistics for smoking prevalence, but no studies to link the two.

Regardless, Gonzalez says that there is no doubt that smoking is a pressing problem for children on multiple levels. “[Secondhand smoke] carries [the] same 7,000 chemicals and 70 carcinogens which can create havoc [on] the developing brain and body of a child.”

“Endothelial dysfunction (stiffening of the arteries and plaque formation) starts in childhood due to repeated exposure to [secondhand smoke] and [is] aggravated when the child starts to smoke. [H]ence, the incidence of cardiovascular diseases are now being reported at an early age,” she continued.

Children are the ultimate — and most powerless — victims of cigarette smoke. “It’s not the children’s fault, but they bear the burden. It’s not their fault. That’s why we have to really control tobacco so we can prevent those outcomes and stop it from continuing to the next generation,” said Gonzalez.

Protecting the young, helping the poor

The Sin Tax Reform Law (Republic Act 10351) appears to be effective enough as a control measure. Signed in December 2012, the law increased and simplified tobacco tax rates, channeling revenue into healthcare. Primarily a health measure, the logic behind the Law is clear: Increase tobacco prices to curb its usage.

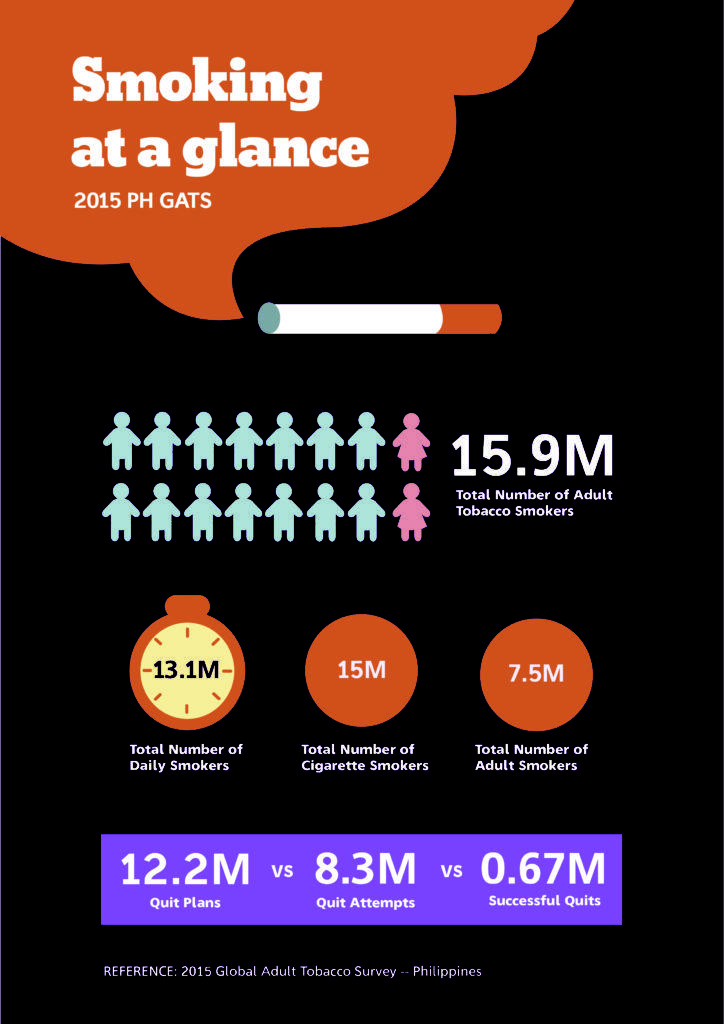

Since its passage, the country has seen significant drops in tobacco use. Results from the most recent Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) showed that from 28.2% in 2009, adult tobacco smoking fell to 22.7% in 2015 – a 19.8% relative decline which experts attribute squarely to sin taxes.

According to the same report, 63.8% of smokers attempted to quit the habit because of the higher prices while 82.3% resorted to lower cigarette consumption, further underscoring the value of tax increases as a disincentive for smoking.

Illustration by Kel Almazan

Nevertheless, there are still nearly 16 million smokers in the country who collectively consume 179.85 million sticks of cigarette in a single day, according to the third Tobacco Control Atlas of the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance. Almost half of them fall between the ages of 25 and 44, prime reproductive age.

Worse, these numbers will almost certainly inflate without tax rate adjustments. “We estimated that if we just maintain status quo, we will have 1 million more smokers by 2022,” laments Ms. Jo-Ann Diosana, Coordinator for Fiscal Policy Programs of the Action for Economic Reforms.

“The 4% increase every year, that’s a good feature but it’s not enough,” she adds. “Before, we just focused on reducing smoking prevalence, but when you look at the absolute number, even if smoking prevalence decreases, because the population is continuously growing, [the number of smokers will increase].”

On a daily basis, millions of adults inhale plumes of cigarette smoke, gradually eroding their genetic material. In a couple of years, thousands more children will be born carrying scarred DNA and a higher risk of severe chronic conditions.

Sadly, this is an eventuality that the policies and healthcare system at large, in their current state, seem unprepared for.

A day-to-day struggle

Lost in all the preoccupation with deterrence and statistics is something very important to Malubay, and others like her who fell through the cracks of the government’s preventive mechanisms: the individual patient experience.

What they want, Malubay says, is something far simpler, something pragmatic: more efficient patient management and more funds available.

Their hospital bills cost a lot. In under a year, she estimates to have spent upwards of a hundred thousand pesos, excluding food and transportation. Fortunately, many government agencies and politicians offer financial assistance to indigent families in the form of guarantee letters. But Malubay says they aren’t enough to accommodate everyone and don’t cover the expenses of daily living.

To make things worse, as a single mother, she can’t keep a steady job and still make it to every doctor’s appointment, especially when hospital trips take an entire day.

During his routine check-ups, Vinz and his mom usually leave for the Philippine Children’s Medical Center by 4 AM. By the time they make it back to their home in Brgy. Pansol, Quezon City, the sky is dark and the sun has long since set. They essentially spend an entire day in line for a blood test and maybe around 15 minutes of consultation.

But more than anything, Malubay just wants the cancer gone. She wants her son to be truly, completely free of it. “I always tell him to get well so that he can go to school, find a job, and be able to buy the things he wants to buy,” she shared. “I want him to have fun like I did – to work hard and enjoy on the side a bit.”

When he grows up, Vinz says he wants to be a soldier or a cop. He likes toy guns a lot, and his mother says he has at least six of them at home. Unfortunately, his dreams will have to wait 3 to 5 more years, the minimum amount of time to finish the entire ALL treatment process. Unfortunately for Vinz, he cannot start schooling while he still has leukemia.

In the meantime, Vinz and his mother are putting all of their time and energy into making sure that he stays healthy, in preparation for his next treatment. –MF

Photo: Tristan Mañalac

This story was produced under the ‘Mga Nagbababang Kuwento: Reporting on Tobacco and Six Tax Media Training and Fellowship Program’ by Probe Media Foundation, with the support of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

Online references:

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/about/what-is-all.html

- https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20369083

- https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/patient/child-all-treatment-pdq

- http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/acute-lymphoblastic-leukaemia-all/getting-diagnosed/tests/bone-marrow

- http://discovermagazine.com/2014/julyaug/18-body-of-work

Author: Tristan Mañalac

Tristan is a journalist based in Metro Manila, focusing mainly on health, science, and the environment. He writes daily clinical news for MIMS.com and does in-depth reporting on the side. Being formally trained in the life sciences, he once dreamed of starting his own lab. But these days, he finds his greatest joy in a bottle of beer and a beautiful sentence.