Concealed in the rainforests of Baras, Rizal, award-winning conservation site Masungi Georeserve gives home to more than 400 species of flora and fauna. Among these, around 70 are endemic to the Philippines.

Masungi’s name comes from the word “masungki” or “sungki,” which means “pointed” or “spiked.” It’s a fitting description for its vast 60-million-year-old limestone formations, which were forged during the Paleocene Epoch.

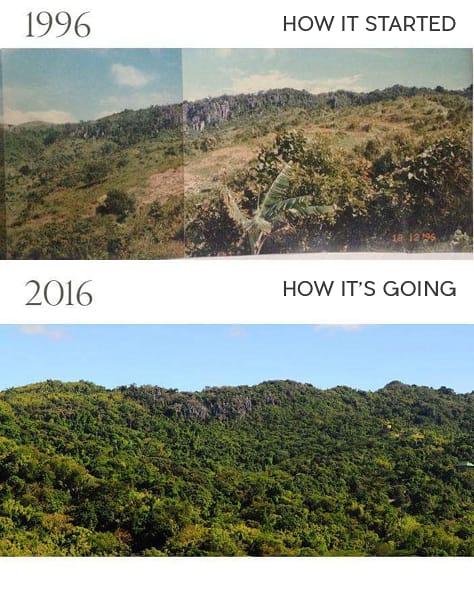

The conservation effort started in 1996, when the government decided to push through with a joint venture project together with Blue Star Construction and Development Corporation. The goal was to restore the 400-hectare karst landscape, while utilizing 30 percent of the area for sustainable development.

Prior to this, the lands that now enclose the Masungi Georeserve used to be heavily deforested due to widespread and massive illegal activities. Two decades later, the Masungi Georeserve Foundation was established to ensure the sustainability of the conservation efforts.

“In 1996, there was so much to be done. The entire area was severely damaged. I think it was chosen to be restored and protected because it’s threatened and vulnerable, and because of the presence of limestones. It has the largest spine of exposed limestones from the Paleocene age in the country,” Billie Dumaliang, trustee of the Masungi Georeserve Foundation, Inc. told FlipScience.

In 2016, the site was opened to the public for geotourism purposes, following a low-impact, high-value approach in line with the UNESCO Geopark Model.

The following year, the foundation took its purpose to another level when it said yes to the late Environment Secretary Gina Lopez’ request for help in the restoration of 2,700 hectares of damaged land within the Upper Marikina Watershed, Kaliwa Watershed, and the Masungi Wildlife Sanctuary.

The parties signed the 2017 Protection and Conservation Memorandum of Agreement between the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the Masungi Georeserve Foundation, Inc. in parts of the Upper Marikina River Basin Protected Landscape in Baras, Rizal.

“Secretary Gina saw Masungi and was happy. She saw all the efforts done to conserve and protect Masungi and she wanted our help to also restore the surrounding areas,” Dumaliang said.

True to its mission of bringing life back to natural habitats, the foundation has expanded its reforestation activities together with different stakeholders. As of today, the foundation has rescued 2,000 hectares from illegal activity and planted more than 60,000 native trees. These trees include the White Lauan, a native premium dipterocarp species; Malaruhat, a native evergreen that can grow up to 15 meters high; Salinggogon, a deciduous tree that can grow up to 45 meters and is remarkable for its pink flowers and characteristics that help prevent soil erosion; and the Antipolo, a tree endemic to the Philippines that is used for pulp and paper production.

The project is still a grassland, the secondary stage of forest succession, and has a long, long way to go before the land fully heals and turns into a mature forest — the main reason why the foundation is bent on putting an end to all environmentally harmful activities.

Twenty years of dedication and hard work to protect the landscape have been surely paying off, though, as evidenced by the abundance of biodiversity there. Here are six species endemic to the Philippines found in the Masungi Georeserve.

1. Masungi Microsnail (Hypselostoma latispira masungiensis)

In 2017, a group of researchers from the University of the Philippines Los Banos was surveying land snails in the area. They spotted a tiny species with an ant-sized, upside-down shell crawling along the limestones.

Because of its similarities to Hypselostoma latispira, a microsnail discovered in Baguio City, the researchers initially believed that it was the same species. However, further studies of its shell morphometrics and shape confirmed that it was, in fact, a subspecies. The Masungi microsnail’s shell is slightly wider (4.5-5 mm) compared to the Baguio microsnail’s (4.2-4.5 mm). It also has a larger body whorl and apertural width.

According to the foundation, the researchers continue to conduct more studies about the Masungi microsnail. Their most recent visit to the area was just in February 2021.

2. JC’s Vine (Strongylodon juangonzalezii)

This species was first discovered in 2015 by a group of researchers from the University of the Philippines Los Banos’ Institute of Biological Sciences and Museum of Natural History, during a floral inventory at the Buenavista Protected Landscape in Mulanay, Quezon.

They came across a Stronglylodon species, a large and irrepressible tropical climbing vine that can grow up to 18 meters long. They noted that the vine had traits inconsistent with other species. It has a “plagiotropic dense inflorescence with 27 to 31 flowers per cluster in a lateral branch.” It is also colored lilac and becomes blue as it matures, compared to other species that retain the same color from budding to opening stage.

Strongylodon juangonzalezii, the eighth of its kind endemic to the Philippines, is also known as JC’s vine. It was named after Dr. Juan Carlos Tecson Gonzales, director of the Museum of Natural History and one of the country’s Ten Outstanding Young Scientists in 2011.

3. Bagawak-Morado (Clerodendrum quadriloculare)

The Bagawak-morado is a critically endangered shrub that can also grow into a small flowering tree. Among its ovate green leaves with dark purple undersides bloom long clusters of white or pink flowers filled with nectar. The flowers are like cotton buds in their early stages. They become more beautiful when they blossom, looking much like a fireworks display.

The species is fast-growing, highly reproductive, and adaptable to different environments. Because of its appearance and attractiveness to butterflies, birds, and bees, the Bagawak-morado is often used as an ornament. In the Philippines, it is also used as an alternative medicine to treat wounds, indigestion, abdominal pains, and ulcer.

4. Luzon Tarictic Hornbill (Penelopides manillae)

The Luzon tarictic hornbill is found in Luzon, Pollilo, and nearby islands. It lives in primary rainforests, riverine forests, and fruiting trees in grasslands, and survives by eating figs, fruits, insects, and other smaller animals.

This bird has a prominent ridged bill, and can easily attract attention due to its multi-colored head and upper body. The males have cream coloration in their head, neck, and underparts, while the females are colored brown or black.

In 2019, the DENR classified the Luzon tarictic hornbill as vulnerable, due to the decline in its population over the past years.

5. Northern Indigo-banded Kingfisher (Ceyx cyanopectus)

The Indigo-banded Kingfisher is another species living exclusively in the Philippines. It is a small, beautiful bird, only about 5 inches in size, sporting brilliant sapphire plumage. What’s more striking is that its blue appearance is due to light reflection caused by a transparent material on its feathers.

It lives in subtropical or tropical dry and mangrove forests, and feeds on fishes and aquatic insects. It has two subspecies: the nominate race (Ceyx cyanopectus cyanopectus) found in Luzon, Polillo, Mindoro, Sibuyan, and Ticao; and Ceyx cyanopectus nigrirostris, which can be seen in Panay, Negros, and Cebu.

6. Philippine Hawk-eagle (Nisaetus philippensis)

Also known as Mulawin, the Philippine hawk-eagle is a bird of prey that can only be found in the country. It catches and feeds on smaller animals with its huge, crooked beak and sharp talons. It lives in primary and secondary forests, as well as in lowlands and mountains. The top of its body is dark brown, and it has a long crest with black feathers. Its throat is white with black streaks, while its lower body is brownish-red. It can weigh up to 1.2 kilograms, and its broad and round wings can span up to 125 centimeters.

The Philippine hawk-eagle is regarded as an endangered species due to hunting and habitat loss caused by illegal logging. But in Masungi, these birds can be seen in flocks or families.

Dumaliang is optimistic that there are “hundreds more species,” some of which might be endemic only to the country or to Masungi, that are still waiting to be discovered, given that a large portion of the landscape and its surrounding areas have yet to be fully explored.

She also shared that there are a number of studies being conducted in partnership with local scientists. Among them are studies on tardigrades, microscopic eight-legged animals that look like bears, as well as research on insect biodiversity, aquatic bugs in the rivers and streams, and mushroom diversity.

Challenges to reforestation

It’s impossible to talk about the richness of biodiversity while ignoring the threats to its protection. According to UK-based watchdog Global Witness, environmental workers in the Philippines constantly receive threats and harassment, making the country one of the deadliest countries for land defenders.

The use of intimidation is not new to the group behind the Masungi Georeserve. Since the project’s establishment, the team has faced off with small and large-scale land grabbers, quarry operators, illegal loggers, and other violators. Some of these disputes were even brought to court.

An article published on the Masungi Georeserve’s website recounted the story of the most recent one, which involved private companies Rublou Inc. and Green Atom Renewable Energy Corporation. According to the report, three individual complainants sought to nullify the 2017 Protection and Conservation Memorandum of Agreement between the DENR and the Masungi Georeserve Foundation, Inc. The said groups reportedly went as far as deploying armed guards and barricading large tracts of the Upper Marikina Watershed. The companies claimed that Green Atom’s chairman, a retired police general, had purchased “a minimum of 300 hectares of the critical watershed” from “settlers and indigenous persons.” However, elders and members of the Dumagat-Remontado tribe of Antipolo (whom the complainants claimed to represent) denied that they had full knowledge of these actions or involvement in the deployment of guards.

In April 2021, the Regional Trial Court of Morong dismissed the civil case filed by the said entities. The court cited the absence of capacity to sue on the part of the complainants, particularly the authority and legitimacy of certain individuals to represent the indigenous tribe.

Dumaliang also talked about how environmental plunderers, who operate as syndicates, use social media to orchestrate and spread disinformation and false propaganda to discredit years of restoration work and sow division among communities. That is why the foundation recognizes the importance of science communication and education.

In the larger picture, the foundation remains optimistic that the local and national governments will continue to make good on their promises to strengthen the enforcement of environmental policies and punish violators to the fullest extent of the law.

Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu had already ordered the immediate closure of quarries and mining activities, as well as the cancelation of all Mineral Production Sharing Agreements issued in the protected areas surrounding Masungi, as early as March last year.

In December 2020, the DENR formed four composite teams to look into the quarry operations in the Rizal area, following the extensive flooding and devastation experienced by some areas in the province and the City of Marikina from Typhoon Ulysses.

However, the situation on the ground begs the question of whether these actions are enough. Massive environmental degradation persists, and exploiters have yet to be booted out of the protected domains completely. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the foundation said that they saw a rise in cases of illegal logging, charcoal-making, and illegal occupation in reforestation areas.

“We are compelled to talk about encroachments. Because if we turn a blind eye, if we back down, we fail to do our purpose to take care of the forests,” said Dumaliang. —MF

On July 24, 2021, a week after the interview with FlipScience, two of Masungi Georeserve’s forest rangers stationed at a reforestation site in Sitio San Roque, Barangay Pinugay were attacked. One was shot in the head and the other was shot in the neck. Both have survived the ordeal, and are being treated in a hospital as of writing. The attack came after the Department of the Interior and Local Government recommended the filing of criminal and administrative charges against government officials and private entities for continuous violations of environmental laws in the protected watershed areas of San Roque, Baras, Rizal.

References

- About Us, Masungi Georeserve

- Information Kits, Masungi Georeserve

- A new subspecies of microsnail from Masungi Georeserve, Rizal, Philippines, Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology, September 2020

- New snail subspecies with ‘upside down shell’ found in last green frontier east of Manila, Mongabay.com, December 1, 2020

- Strongylodon juangonzalezii, a remarkable new species of Strongylodon (Fabaceae) from Mulanay, Quezon Province, Philippines, PhytoKeys 73(Part 2), October 2016

- New species of Strongylodon described by Museum botanists, UPLB Museum of Natural History, October 19, 2016

- Strongylodon macrobotrys, Plants of the World Online

- Clerodendrum quadriloculare, Conservatory of Flowers

- Clerodendrum quadriloculare (bronze-leaved clerodendrum), Invasive Species Compendium

- THE ANTISPASMODIC EFFECT OF Clerodendrum quadriloculare (Blanco) Merr. LEAF EXTRACTS, International Journal of Pharmacy, January 2015

- Luzon Hornbill Penelopides manillae, BirdLife International

- Luzon Hornbill, Project NOAH

- Indigo-banded Kingfisher, Avibase

- Indigo-banded Kingfishers, Beauty of Birds

- Philippine Hawk-eagle, Avibase

- Philippine Hawk Eagle – Nisaetus philippensis, The Eagle Directory

- Defending Tomorrow, Global Witness, July 2020

- Enemies of the State?, Global Witness, July 2019

- Court junks bid to stop watershed protection efforts, Masungi Georeserve, May 10, 2021

- Quarry firm encroaching into Masungi Geopark faces closure, Department of Environment and Natural Resources

- DENR News Alerts, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, December 11, 2020

- TWO FOREST RANGERS SHOT AT BAYOG RANGER STATION NEAR GSB RESORT, Masungi Georeserve

- DILG PRESS RELEASE, PR Code No. 2021-07-14-01, Department of the Interior and Local Government

Author: Jil Danielle Caro

Jil Danielle M. Caro is an Information, Tourism, Culture and Arts Officer at a local government unit. She is also working as a business and science journalist on the side.

She is a graduate of B.S. Development Communication from the University of the Philippines Los Banos and is about to pursue her Master of Arts degree in Philippine Studies at the University of the Philippines Diliman.