•Based on specimens from Cebu, the Conus imperialis cone snail may be using its venom not to incapacitate its prey, but to lure it—a move the researchers nicknamed “the King’s Gambit.”

•Two of the snail’s chemicals, conazolium A and genuanine, were incredibly close mimics of the pheromones that initiated mating rituals among Platynereis dumerilii worms.

•The study also revealed noteworthy differences between deep-water and shallow-water C. imperialis, suggesting that they might actually be separate species.

When cunning and creativity come together in nature, it often happens in the most horrifically fascinating ways. This is particularly evident in marine predation: There are sea slugs that store and weaponize their extremely toxic prey’s own venom, fishes with four “eyes” that help them catch bugs on sandbanks, and wrasses that extend their mouths from their bodies a la Alien (which is exactly as terrifying as it sounds).

And if recent findings based on samples from Cebu are any indication, we might be able to add “cone snails that catfish shy worms in heat” to that list.

Mirror move

In a study published on March 12 in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances, scientists from the United States, Denmark, Australia, and the Philippines collected and analyzed specimens of Conus imperialis, a type of marine mollusk scattered across the Pacific Ocean.

Cone snails hunt using a combination of powerful venom and a needle-like radula (think of it as a cross between a tongue and a tooth), going full Captain Ahab on worms, fish, or even other mollusks.

Despite making up the bulk of identified cone snail species, it’s the worm-eating types like C. imperialis whose behaviors we know little about. And because the short strings of amino acids (peptides) in their venom show promise in drug discovery and development, the researchers decided that their hunting methods merited a closer look.

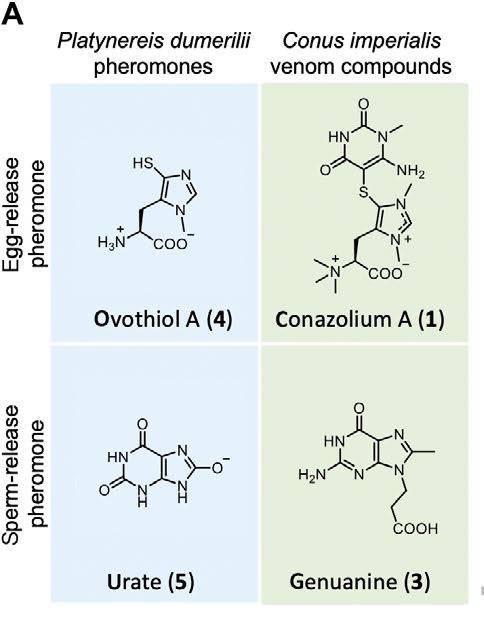

After isolating the molecules in C. imperialis‘ venom gland, the team found two compounds that caught their attention. Both molecules, conazolium A and genuanine, possess a curious characteristic: they’re respective chemical mimics of ovothiol A and urate, pheromones that play a major role in the reproductive process of Platynereis dumerilii polychaete worms.

Sudden death

Worms like P. dumerilii hide in tiny underwater gaps most of the time, but come out of the seafloor during their mating cycle. When it’s time for them to, ahem, get some lovin’, the worms perform a sort of mating dance: the female swims around in tight circles as the male releases sperm. The release of the aforementioned pheromones kick off this ritual.

Thus, the team formed a hypothesis: the pheromone-like conazolium A and genuanine in C. imperialis‘ venom aren’t meant to impair their prey’s functions, but to bamboozle them into a “dinner date” that features them as the main course.

Or, as explained by Dr. Joshua Torres, a Filipino medicinal chemist at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of the study: “This particular species has deciphered the chemical cues that their prey use during mating, and use it for hunting them.”

In controlled experiments, the team observed that in most instances, P. dumerilii males and females began their mating ritual when the chemical mimics were released in their petri dishes. Interestingly, the snail chemicals actually lasted longer than the real pheromones, which degrade rapidly upon release.

“The mimics trick worms into prospects of mating, only to be lead to their demise,” said Torres. “I think the sophistication that the snails use in trying to create prey capture strategies is pretty fascinating.”

Round robin

It’s worth noting that scientists aren’t sure if C. imperialis actually eats this specific type of worm. However, genetic material from some closely related species were found in the mollusk’s gut. If anything, this suggests that C. imperialis uses these chemicals on P. dumerilii‘s relatives (perhaps the more accessible ones).

“As there are about 1,000 different species of cone snails, one can expect many different hunting strategies out there,” clarified Torres, who added that future researchers should try filming aquariums with worm-hunting snails and polychaete worms to see how the former would behave in the presence of the latter.

However, he also emphasized that field experiments, which would involve being at the right place at the right time, are still the best way to do this.

“Although [the aquarium setup] may closely model what it is like in nature and still provide scientists control over certain variables, you’d still lose certain elements that lab setups can’t simply capture.”

Black and white?

The researchers even gave the snail’s sly strategy a nifty nickname: the King’s Gambit, after a well-known opening chess move that uses two pawns (like how C. imperialis uses its two chemical mimics).

Torres revealed that it was the snail’s crown-like shape that sparked the idea—though the mimic moniker is far from the only thing that its spire inspired.

Torres and the team noted physical differences between deep-water specimens and shallow-water specimens. The snails that came from deeper waters were smaller, with more pronounced spires; they also had slightly different shell patterns from their shallow-water ilk.

Additionally, the shallow-water specimens had dark red distal venom glands, as opposed to the deep-water specimens’ greenish yellow.

The most profound difference, however, was chemical in nature: Instead of conazolium A, the shallow-water C. imperialis produced serotonin- and glutamate-like neurotransmitters. In other words, their hunting styles may actually be completely different.

The researchers are currently collecting more of these snails, pandemic challenges notwithstanding, to determine whether these C. imperialis variants should be classified as separate species.

“We are also trying to look at the other species of cone snails, including the fish- and mollusk-hunting ones,” shared Torres.

Stalemate

With all this talk about predator creativity, it’s easy to forget that prey can be quite crafty, too. According to Torres, different types of prey have also evolved evasion strategies, including chemical weapons, to fight back.

“Marine animals like bryozoans protect their developing babies (which are totally exposed to the elements) by lacing them with extremely toxic chemicals, possibly to deter potential predators.”

These toxic chemicals, called bryostatins, are currently in advanced stages of clinical trials, with researchers examining their therapeutic potential against cancer. For Torres, this demonstrates precisely why it’s important for medicinal chemists, biologists, and neuroscientists to study these marine animals.

“Understanding these molecules in full detail—who makes them, how they are used, and so on—allows us to better design the many life-saving drugs that we are using now, and that we will be needing in the future.”

Reference

- https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/advances/7/11/eabf2704.full.pdf

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.