Nearly 15 years ago, for 10 glorious minutes, science fiction became a living, breathing reality.

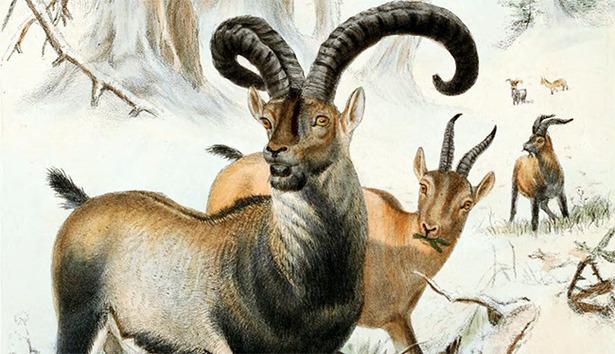

On July 30, 2003, scientists from France and Spain witnessed a truly historic moment in the field of genetics. Three years earlier, the last Pyrenean ibex, Celia, met her end under the weight of a fallen tree. Her cells, harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen, were implanted in a Spanish ibex-goat hybrid female. On that fateful day, the female gave birth to Celia’s clone, the only successful attempt out of 57. Unfortunately, the calf had a respiratory condition that almost immediately proved to be fatal. Talks of another attempt at resurrecting Celia’s ilk made the rounds in recent years. However, due perhaps to the concerns raised re: the viability of Celia’s genetic material after an extended period of cryopreservation, nothing new seems to have materialized as of today.

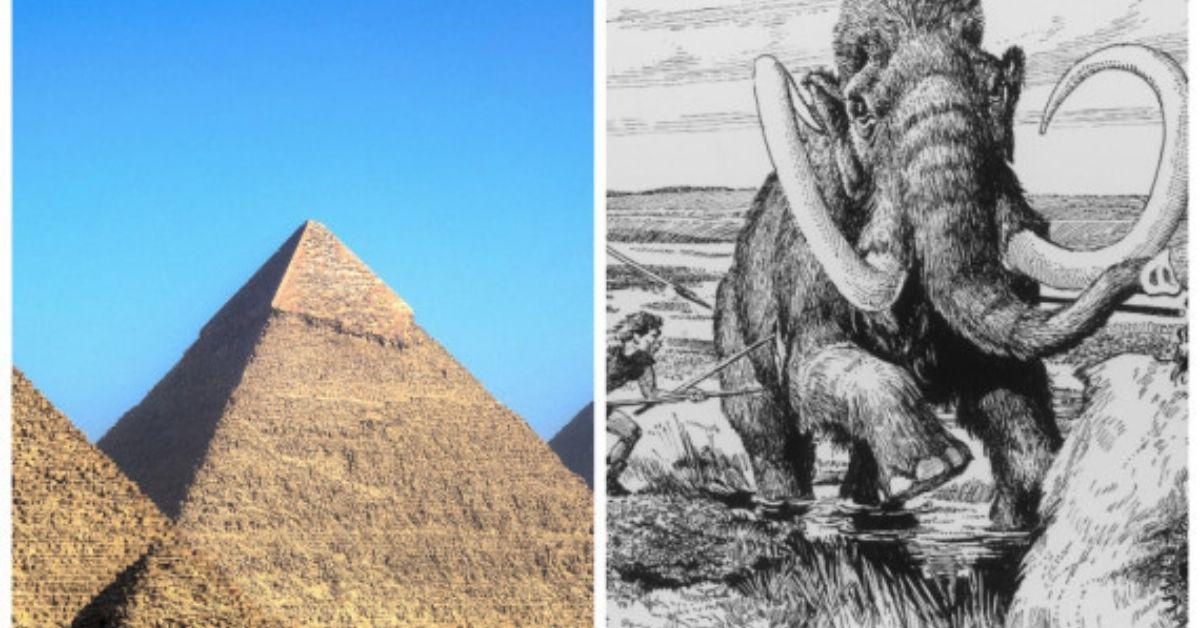

This setback, though, has not completely discouraged scientists from trying. The woolly mammoth, the passenger pigeon, and the thylacine are just some of the many species that are being considered for de-extinction.

The question surrounding bringing these species back to life is twofold: Can we? And should we?

Bringing the extinct back from the brink

To understand how scientists can restore these extinct animals, one must first understand the necessary components of such an undertaking.

As explained on The Hindu, one method of de-extinction, somatic cell nuclear transfer, involves fusing together the donor cell’s nucleus and an egg cell that has been enucleated (i.e. has had the nucleus removed). This process requires living cells from the extinct animal, which, in the case of many species — such as those of the dinosaurs, by far the most popular subject of these discussions, due in no small part to their significance and presence in pop culture — are simply unobtainable. Enzymes, microorganisms, and radiation had already broken down the DNA found in these species’ bones and teeth over millions of years.

De-extinction may still be possible, however, despite the lack of intact or living cells. One way is to create a genetic blueprint that resembles the extinct species as closely as possible, based on the modified genome of the species’ closest living relative. The second involves taking portions of the genome of the closest living relative and exchanging them with portions from the extinct species’ genome. An example of the second: efforts to revive the woolly mammoth using DNA from the Asian elephant.

Still, another technique is through selective breeding. After discovering that the quagga was actually a subspecies of the plains zebra, interested parties launched and funded The Quagga Project in 1987, which selects zebras with distinguishably quagga-like characteristics and breeds them, in the hopes of eventually producing offspring that are as close to the extinct animal as possible.

De-extinction may be possible, but for what purpose?

The idea of reviving species long gone enjoys popularity and support for a multitude of reasons. First, the de-extinction of an entire species would be a remarkable feat in itself. Furthermore, some of these animals played crucial roles in the ecosystem during their time on Earth — roles that they could resume upon the repopulation of their species. De-extinction is also seen by some as a means of making up for the mistakes of our ancestors due to greed, superstition-fueled ignorance, or a general lack of understanding of how the balance of life works.

Critics of de-extinction, however, bring up a number of points that are quite valid. For instance, how well would these revived species fare in present-day atmospheric and geological conditions? What really drives the desire to bring them back from oblivion? Is it mere scientific curiosity? Is it in fulfillment of an urgent ecological need that no other living species could fill? Or is it simply for entertainment — to satisfy our selfish dream of a real-world Jurassic Park?

One thing is certain, though: The successful de-extinction of a species would be yet another giant step for science and for mankind. Mammoth-sized, even.

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.