It was midnight. At this ungodly hour, my orgmates and I were sitting in an open terrace, attempting to settle internal matters via a lengthy meeting.

Taking advantage of my peers’ unbelievable attentiveness during the discussion, I did what any bored and sleepy person would do: stare idly. (I’m not making excuses for myself here; I’m just not a night owl.)

My eyes surveyed the landscape around us. Soon enough, I found myself staring at the twinkling dots above.

Of course, I’m not the first person to feel awestruck and small by looking at the stars. In fact, humanity has exhibited this fascination throughout much of the world’s history. Humans observed them, counted them, made music and wrote poetry about them, and even worshipped them.

Unsurprisingly, our ancestors were no exception.

Filipino ethnoastronomy: staring at the stars

In 2005, Dr. Dante Ambrosio—who many recognize as the Father of Philippine Ethnoastronomy—published his journal article BALATIK: Katutubong Bituin ng mga Pilipino. In a nutshell, ethnoastronomy focuses on people’s understanding of astronomical phenomena in their own cultural context across time.

While astrologers see stars as the window to the future, Ambrosio presented the sky as a sure door to our distant past. He wrote that long before Europeans stepped on our soil, we already had our own constellations. Given the diversity of the pre-Hispanic Philippines, he was able to find numerous constellations from various ethnic groups around the country.

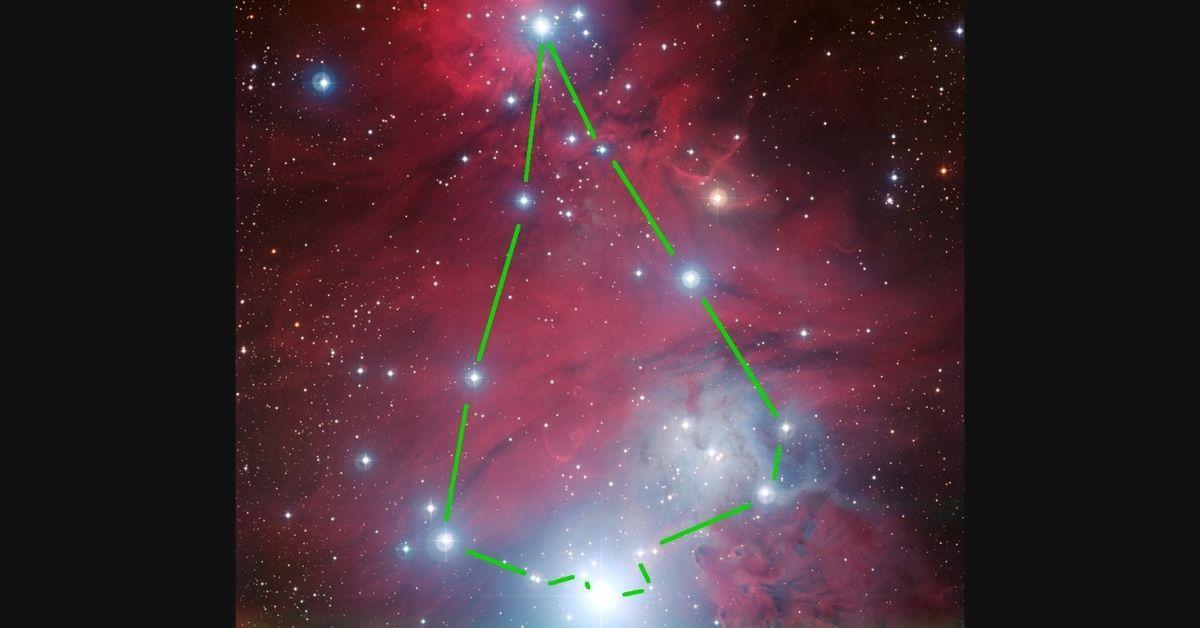

However, two constellations stood out throughout the archipelago: Balatik and Moroporo. For our ancestors, these well-known stellar formations marked the seasons of hunting, planting, and sailing.

[Philippine Ethnoastronomy #1: Balatik and Moroporo]

Even before the Spaniards came to the Philippines, Filipinos have…

Posted by Egg nebula on Friday, August 2, 2019

Starstruck

If we were to interpret the functions of Balatik and Moroporo without considering their cultural signicance, we’d miss much of the bigger picture. As Dr. Ambrosio put it, ancient Filipinos “claimed the sky as their own and put their own distinctive marks on it.”

Take Balatik, for example: Whereas the Greeks witnessed Orion’s belt, some of our ancestors saw a hunting trap from the same stars, reflecting their life within hunting and gathering societies.

As for sailing: According to Diane Manzano, a language professor from UP Los Baños’ Department of Humanities, ethnoastronomy guided our ancestors, who were extremely good sailors.

“We were good navigators, and our life was connected to the sea. This is very important, because somewhere along the way, we forgot how good sailors our ancestors were and we forgot that our seas and rivers connected our cities and barangays,” she said.

Aside from that, they also used the stars to immortalize their ideals in the evening sky. By weaving constellations into myths, ethnic groups remembered their collective aspirations by just looking up at night.

The Teduray, for example, tells of the bravery and strength of the hunter Seretar (Orion), when he killed a pig and left its baka or jawbone (Hyades) for kufukufu or flies (Pleiades) to feast upon.

Starburst

But wait—if we were always so acquainted with the stars, what changed?

According to Ambrosio, our current way of mapping them provides some clues. By the 16th century, we had already identified several constellations using Spanish names—a sign of colonization. Today, our taken-for-granted familiarity with Greek constellations (and unfortunately, ignorance of our own) signals the triumph of modern astronomy.

If the stars are indeed key to our history, then we have a serious problem.

“Ang pag-aaral ng etnoastronomiya ay importanteng ambag sa nation-building dahil nagpapatunay ito na hindi salat ang sinaunang Pilipinong lipunan sa siyensya at teknolohiya. If we do not know our history, paano natin malalaman ang identity natin bilang mga Pilipino?” asked Manzano.

(“The study of ethnoastronomy is an important contribution to nation-building, as it proves that ancient Filipino societies were not lacking in the fields of science and technology. If we do not know our history, then how can we possibly know our identity as Filipinos?”)

In other words, the absence of ethnoastronomy from our collective memory would erase a deep sense of who we are.

Starry-eyed

Furthermore, Manzano explained that modern astronomy, with its emphasis on the Western “system of thought,” has displaced indigenous knowledge systems like ethnoastronomy.

Pecier Decierdo, The Mind Museum’s resident astrophysicist, affirms this; however, he also offers an explanation. Modern astronomy found ancient Greece’s star lore useful because of its being “frozen in time” (which Manzano attributed to writing and the printing press). In contrast, other early conceptions of the heavens, like ours, were largely transmitted through oral history.

Both Manzano and Decierdo agree that our ignorance of ethnoastronomy points to a sad reality: We have lost our connection with nature. Meanwhile, our ancestors—and even the indigenous Filipino communities of today—highly prized the stars for their role in their daily lives.

“We cannot even see most stars at night from where we live,” said Decierdo. (Thanks to light pollution, this truly is the case, sadly. Remember that meeting I mentioned earlier? It took place in the countryside, far away from my hometown in Metro Manila.)

Our apparent amnesia, according to Manzano, is also partly due to the failure of the academe to effectively share its findings to Filipinos outside its halls.

Written in the stars

But will studying ethnoastronomy help us in advancing modern astronomy? “In terms of cutting-edge astronomy, maybe not so much,” said Decierdo.

Despite this blunt admission, there’s a good reason why we should care about how our ancestors saw the stars.

“Even the most cutting-edge modern astronomy traces its roots from the deeply and universally human desire to understand the rules that govern the universe and our place in it,” he said.

Perhaps, this universal curiosity explains why I felt awe upon looking at the stars. While it’s true that these bright wonders have long been part of our historical tapestry, staring at them just never gets old.—MF

References

- https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/pssr/article/view/1287

- https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9781461461401

Author: Cesar Ilao III

Cesar III is currently a BS Development Communication student from the University of the Philippines Los Baños. As a science communicator, he is passionate about sharing science to all Filipinos.