Having grown up as someone with a sense of direction that constantly needs… well, direction, I definitely appreciate accurate, well-made maps. Until the pandemic that has forced all of us to stay indoors, I’ve been reliant on digital navigation tools to make sure I wouldn’t get lost on my way to where I’m supposed to be. I’ve always dreaded the prospect of finding myself in the middle of nowhere, with no clue as to how I got there or where I should go next. Apps like Waze and Google Maps have saved me countless times from confusion, distress, and downright embarrassment.

Thus, it’s shocking to me that all over the world, volunteers who provide medical aid to impoverished towns and war-torn villages often rely on maps like these, out of necessity:

The absence of reliable maps makes it challenging for relief aid providers to reach areas in dire need. Aside from running the risk of not making it to their destination in time, these volunteers may even find themselves in harm’s way, as they traverse unfamiliar paths and have no idea what’s in store for them. Having resources that can tell them which paths to take and which areas to avoid is a massive boon for these humanitarian efforts. And so, when I heard about an opportunity to help them in helping more people, I just had to join.

After all, with a marketing pitch along the lines of “No experience necessary; just prepare your laptop, a mouse, stable Wi-Fi, and your enthusiasm,” how could I not?

Mapping without borders

Last August 1, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) held its first-ever virtual “Southeast Asia Missing Maps Mapathon.”

A humanitarian organization that focuses on bringing much-needed healthcare to victims of crises, MSF’s team works in the world’s most vulnerable—and often unmapped—places. MSF’s field workers (no doubt like many other volunteers and organizations) end up relying on hand-drawn maps like the one shown above. Can you imagine coordinating relief aid operations and disaster response missions with such maps? I sure can’t (and don’t want to), but that’s what makes the commitment of these volunteer groups all the more impressive.

Anyway, to address this, MSF partnered with the British Red Cross, the American Red Cross, and the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) in 2014 to establish Project Missing Maps. Using the power of crowdsourcing, Project Missing Maps produces accurate, up-to-date digital maps of the world’s little-known or “forgotten” areas.

Here’s where the concept of the mapathon comes in. Mapathon volunteers from different parts of the world use the OpenStreetMap tool to trace maps over satellite photos, marking houses, buildings, and other structures. This is helpful, because with the right maps, volunteers can figure out the most efficient paths to get aid to where it’s needed most.

Now, getting the maps published isn’t a quick and easy process; understandably, each map undergoes a two-step validation process by remote experienced mappers, and then by local volunteers themselves (who add the correct labels and other relevant information).

However, thanks to technology, the process of creating the maps has become much easier, and can be done by anyone (including the direction-impaired, like me).

The mapathon I joined, which included participants from Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore, focused on Nigeria. Before this, MSF had already organized 5 public mapathons (with over 600 participants) and 8 corporate marathons in Singapore from 2017 onwards.

Over the past decade, Niger State has been experiencing issues involving lead exposure and measles outbreaks, as well as various health emergencies since 1996. MSF has been working in the area for nearly 50 years now, providing aid during times of conflict and disease outbreaks.

The mapathon experience

The entire mapathon took place via a webinar hosted by MSF. It started by providing some history and context for the activity. After that, they discussed exactly what we were supposed to do.

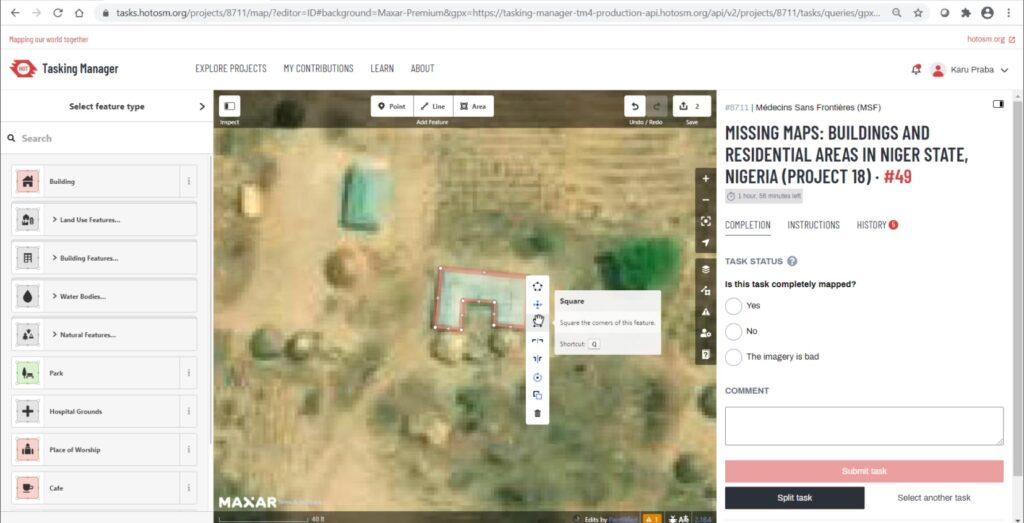

First, we were instructed to set up an account for OpenStreetMap using Google Chrome, Safari, or other similar browsers. Registered users can access the Tasking Manager, which displays ongoing and available projects.

After picking a project, you can choose which area of the map you want to work on.

After a brief primer on the different functions and buttons on the interface, I picked an area of the map and began working.

Using maps generated from satellite data, we had to mark rectangular and circular buildings.

We also had to be careful not to mark trees and other objects by mistake.

Within the platform, special keystrokes make the work shorter and faster. We were also told to input a unique hashtag for the project (#msf_sea) to help the organizers track our progress.

The whole experience reminded me of all those real-time strategy (RTS) games I used to play in high school, with the isometric, top-down map view. Well, minus the soldiers, tanks, and gold mining, but still.

Unfortunately, because I struggled a bit with the controls and decided to switch maps a couple of times (as some of the maps I picked ended up having no buildings whatsoever), I was only able to mark 40 buildings, give or take, before our time was up. Considering the fact that our objective was to map 10,000 buildings by the end of the session, I’m lucky I was in a group of tech-savvy eager beavers who managed to exceed the goal.

Overall, it was an entertaining experience that highlighted the value of technology in relief operations. It’s an activity that I might consider participating in again at some point, mostly because I like helping relief aid volunteers, and partly because I’m somewhat embarrassed by my final building total.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) brings medical aid to people in emergency situations in over 70 countries around the world. For more information on how to participate in future mapathons and the organization’s various initiatives, visit MSF Southeast Asia or send an email to regina.rosero@hongkong.msf.org.

Author: Mikael Angelo Francisco

Bitten by the science writing bug, Mikael has years of writing and editorial experience under his belt. As the editor-in-chief of FlipScience, Mikael has sworn to help make science more fun and interesting for geeky readers and casual audiences alike.